By Scott Richman, RFA Chief Economist

If you watched the Sunday morning talk shows last weekend, you might have noticed a new advertisement (paid for by oil refiners) that attacks the Renewable Fuel Standard. The ad notes that consumers are paying record-high prices at the pump (something that has nothing to do with the RFS), but conveniently fails to mention that refiner profits have hit record-high levels as well. Here’s what’s really going on: as the marketplace anxiously awaits the final RFS volumes for 2020-2022, oil refiners are attempting to divert attention away from their unprecedented profit margins and the impact those margins have on gas prices.

Once again, at a time when ethanol is clearly saving drivers money at the pump, oil refiners and their allies are trying to mislead policymakers and the public about the real causes of higher gas prices.

Recent Price Trajectory

Refining margins have surged over the last few months, due in large part to geopolitical and seasonal factors. Prices of crude oil and refined products had been rising since late 2020 as a result of restrained production—mainly by the OPEC+ group of producers that includes Russia—and the economic recovery that followed the COVID-19 lockdowns. However, the price increase accelerated after Russia invaded Ukraine in February, as the U.S. banned imports of Russian petroleum and as other countries and private companies took steps to limit purchases.

Notably, the prices refiners receive for refined products (primarily gasoline, jet fuel, and diesel) have strengthened considerably more than the prices those refiners are paying for crude oil. Stocks of gasoline and distillates have fallen—particularly on the East Coast—and export demand has risen. Additionally, gasoline prices typically rise in the spring, in advance of the summer driving season.

Refining Margins

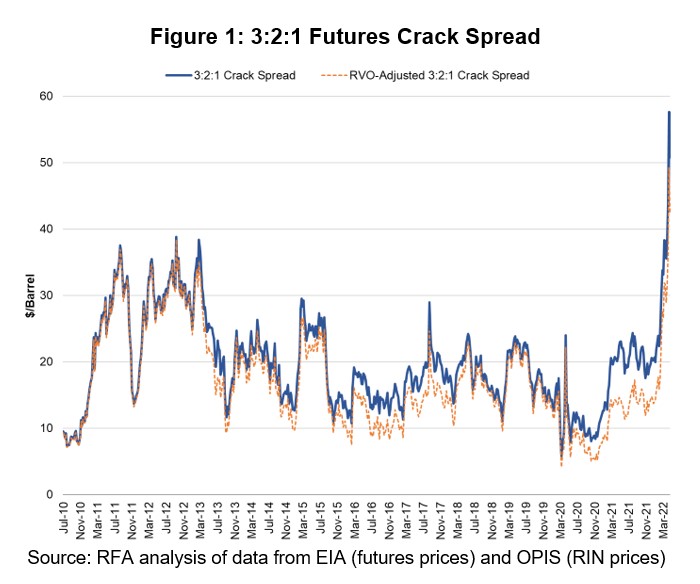

The relative strength of refined product prices is reflected in refining “crack spreads,” defined as the difference between product prices and crude oil prices on a per-barrel basis. The U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) notes, “These spreads are often used to estimate refining margins. … The most common multiple-product crack spread is the 3:2:1 crack spread. A 3:2:1 crack spread reflects gasoline and distillate production revenues from the U.S. refining industry, which generally produces roughly 2 barrels of gasoline for every barrel of distillate.”

The 3:2:1 crack spread reached nearly $60/barrel during the last couple of weeks, which is almost triple the $20/barrel level around which it gravitated from September to January (Figure 1). This spread is calculated using prices of futures for West Texas Intermediate crude oil, gasoline (RBOB) and distillates (ULSD) that are traded on the NYMEX, a part of the CME Group. (The spread would be very similar using Brent crude prices.)

It is also worth noting that the 3:2:1 crack spread would have hit a record level even if it were adjusted for the value of RINs, which are credits used to demonstrate compliance with the RFS. Refiners continuously complain about the cost of RINs; however, it has long been established by the Environmental Protection Agency and academic researchers that refiners recover such costs via the wholesale price of gasoline. In other words, the cost of RINs is embedded in the crack spread.

It is important to note that the refiners’ RIN cost is offset further downstream in the fuel supply chain, meaning the consumer of regular gasoline generally sees no impact from RINs. The EPA recently concluded that biofuel “blenders are passing through 100% of the RIN price as a discount to consumers in the price of blended fuel.”

The consolidated cost of RINs associated with the different categories of biofuels required under the RFS is referred to as the Renewable Volume Obligation (RVO). It applies to each gallon of obligated fuel (gasoline or diesel) sold by a refiner or importer. The 3:2:1 crack spread adjusted for the RVO cost was shown in Figure 1.*

Similarly, the gasoline crack spread, which represents the difference between the price of gasoline and the cost of crude oil on a per-barrel basis, has also hit a record. Figure 2 shows the gasoline crack spread and the adjustment for the RVO cost, as well as an adjustment only for the price of RINs associated with ethanol (so-called D6 RINs). The weekly D6 RIN-adjusted gasoline crack spread also hit a record, meaning gasoline refining would have hit a record even if RIN values were not embedded in the crack spread.

Implications for Refiners’ Compliance with the RFS

In December, the EPA issued proposed RFS volume requirements for compliance years 2020 through 2022. Refiners have criticized the proposal even though it includes two features they requested: 1) a downward adjustment to the 2020 percentage standards that were originally finalized in December 2019, and 2) setting the 2021 volumes to match actual biofuel usage. Only for 2022 does the implied conventional biofuel requirement (the category for which corn ethanol can be used) return to the level that was set in legislation. During the comment period on the proposal, RFA and others advocated for restoration of the 2020 requirements to their initial levels (minus prospective reallocation for small refinery exemptions that are unlikely to be granted).

In 2018 and 2019, RIN prices plummeted due to the previous administration’s unprecedented and wanton granting of RFS compliance exemptions to small refineries. Subsequently, courts have ruled on the EPA’s mismanagement of the small refinery exemption (SRE) program during that period; the EPA has withdrawn 31 SREs that were previously granted for compliance year 2018; and the agency has proposed denying all 65 SRE petitions that were outstanding as of last December.

The EPA’s proposed 2020-2022 volume requirements and its signaling of future limits on the SRE program have been priced into the RIN market. Additionally, as noted above, refineries recover the cost of RINs, and refining margins are at record highs. Accordingly, refiners should stop trying to avoid the use of lower-cost, lower-carbon ethanol and move forward with what’s best for consumers and the environment.

* The RVO can be calculated starting in 2010, when multiple categories of RINs started being traded after the EPA issued a rule implementing changes made to the RFS by the Energy Independence and Security Act of 2007.